Hamstring tension is an exceedingly common musculoskeletal complaint in patients. It rarely has a single cause, but instead, is the end result of several different causal factors.

In this article, I will address some of the common causes of hamstring pain and tension in addition to explaining several effective treatment methods utilised at Chris Gauntlett Myotherapy. Treatment options will include explanations of how Jean-Pierre Barral’s visceral manipulation and neural manipulation techniques can provide long-lasting relief, as well as, covering several home therapies in the form of take-home stretches and exercises that you can implement immediately after reading this article.

Anatomy

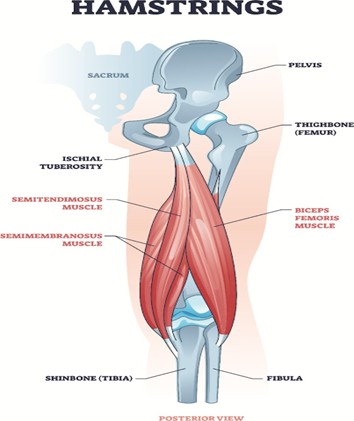

The hamstring muscle group comprises three muscles. They are the biceps femoris, the semimembranosus, and the semitendinosus.

All three hamstring muscles have their origin at the ischial tuberosity, commonly referred to as the ‘sit bone’. However, the short head of the biceps femoris originates from the linea aspera on the posterior aspect of the femur. The biceps femoris inserts onto the lateral condyle of the tibia and the head of the fibula. The semimembranosus inserts onto the medial condyle of the tibia, while the semitendinosus inserts onto the pes anserine on the medial aspect of the tibia.

A significant and unique feature of the hamstring muscle group is that these muscles are one of the few groups in the body that cross two joints. This can make both training and stretching them more complicated, requiring more coordination, as simultaneous control of two joints is necessary for effectiveness.

Common Causes of Hamstring Tension

Rarely is there just a single cause of tight hamstrings. Instead, there is almost always a variety of factors contributing towards hamstring tension. Some of the most common causal drivers are as follows:

Strength Imbalance:

To optimise performance and avoid injury, there needs to be a symmetry of strength between opposing muscle groups. Both in active and underactive populations, hamstring weakness is a significant contributor to tight hamstrings. When the quadriceps (agonist) are too strong – either due to overtraining or undertraining of the hamstrings – and the hamstrings (antagonist) are weak, a protective tension and/or pain in the hamstrings is the result. Another way of thinking about this is that when your engine (quadriceps) is too powerful, and your brakes (hamstrings) aren’t up to the task, then tension, pain and dysfunction are the result.

This strength imbalance can also have profound effects on posture and pelvic alignment, potentially contributing to both back and hip pain/tension. Fortunately, restoring a symmetry of strength between opposing muscle groups is a relatively straightforward process. It involves strengthening the long, weak, and underused muscle group and lengthening the shortened, overused muscle group either through stretching or manual soft tissue manipulation, such as massage.

Below is a short video explaining a couple of simple exercises to strengthen hamstrings that can be done at home without needing fancy gym equipment…

Flexibility Imbalance:

Just as with strength, a symmetry of flexibility between opposing muscle groups is also essential for optimising performance and reducing injury risk. Usually, it is the shortened and overused muscle group that requires stretching. In relation to hamstring tension, the quadriceps muscle

group is most commonly affected. This may seem counterintuitive, as the hamstring muscle group is where people commonly experience tension. Remember, it is often the long, weak, underused muscle that people experience tightness in. This muscle needs to be strengthened, and stretching it will frequently exacerbate the problem!

Below are two short videos covering several approaches for stretching both the hamstring and quadriceps muscle groups:

Hamsting Stretches Video:

Quad Stretches Video:

Body Mechanics:

The human body is a highly complex machine and is incredibly intelligent at adapting to the movement demands that we place on it. Consequently, body mechanics and movement patterns can vary significantly from individual to individual as we adjust to the movement demands of everyday life and exercise. Some movement strategies are less efficient than others. They are sometimes compensations for previous injuries and trauma; other times, they are learned behaviours that we have incorporated into our movement patterns and expression of self.

A typical example of one such movement pattern that can result in hamstring tension is a lack of hip extension when walking and running. When the glutes don’t fire and the hip doesn’t extend, the body finds an alternate strategy for propulsion; in this case, an overreliance on the hamstrings. There can be many and varied reasons for this, including:

- Muscle weakness.

- Muscular tension/restriction.

- Visceral tension/lesions – preventing hip extension.

- Ligamentous restriction.

- Neural tension.

- Vascular tension.

- A learned movement technique or habit.

Careful investigation and analysis are required to establish the primary causal drivers of the movement strategy being utilised by the patient. Restoring optimal and efficient body mechanics typically involves employing multiple treatment approaches, which may include manual soft tissue therapy, movement-based therapy, and/or strength training.

Visceral Lesions and Tension:

For an organ to be in good health, it must be able to move. Every time you take a breath, flex, extend, or rotate your spine, the internal organs must shift to accommodate this movement. When the organs lose this ability, the body ‘hugs the lesion or tension’, to quote visceral manipulation pioneer, Jean-Pierre Barral. This makes perfect sense when you think about it. The internal organs (viscera) are essential for life. Consequently, the body prioritises their health and protection; muscles are sacrificed to protect the organs, resulting in movement restriction and musculoskeletal pain.

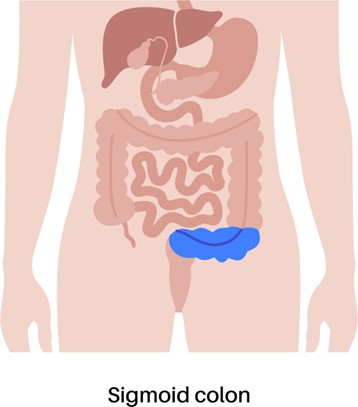

Numerous visceral restrictions can contribute to hamstring tension. A common one is a restriction of the sigmoid colon. See the diagram below.

The sigmoid (highlighted in blue) is located on top of the primary hip flexors in the left hip. When the sigmoid loses the ability to move, the hip flexors – psoas and iliacus – tighten up to protect it. This hip flexor tension restricts hip movement. As we have already discussed earlier, when hip extension is limited, the body recruits more from the hamstrings to compensate, overloading them and creating tension.

The relationship of visceral restriction and tension to musculoskeletal pain and dysfunction is poorly understood by the vast majority of physiotherapists, osteopaths, and massage therapists. Fortunately, the solution to visceral restriction is simple and straightforward. All it requires is a therapist trained in visceral manipulation techniques who can identify the precise cause of the restriction and gently free it. Visceral manipulation is very gentle and will provide much

longer-lasting relief from what is misdiagnosed as muscular pain than conventional muscular massage.

Ligamentous Tension:

Many musculoskeletal therapists don’t even consider ligaments as a treatment option. This widely held view is based on the false assumption that, because ligaments have almost no contractile fibres when compared to muscles, they cannot be treated effectively with manual techniques. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Recent research has demonstrated that ligaments are highly important soft tissue structures for proprioception – your body’s ability to sense movement, action, and location. Consequently, manual treatment of the ligaments can have a profound impact on the nervous system, thereby significantly reducing muscular tension and pain.

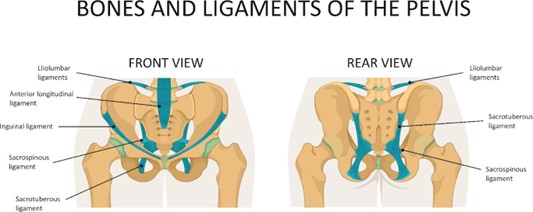

The most common ligaments that I treat in my clinic to alleviate tight hamstrings are the sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments of the pelvis. See the image below.

Both ligaments attach to the ischium, which is also the origin of the hamstring muscles, as discussed earlier. If there is a deeper visceral tension within the pelvis, this tension will almost always be reflected in a torsion and ligamentous tension of the pelvis and sacrum. The hamstrings tighten up in opposition to this and are very much ‘the victims, not the culprits’. Consequently, it doesn’t matter how much you stretch or massage the hamstrings; tension will keep returning until the deeper visceral and ligamentous tension is addressed.

Neural Tension and Restriction:

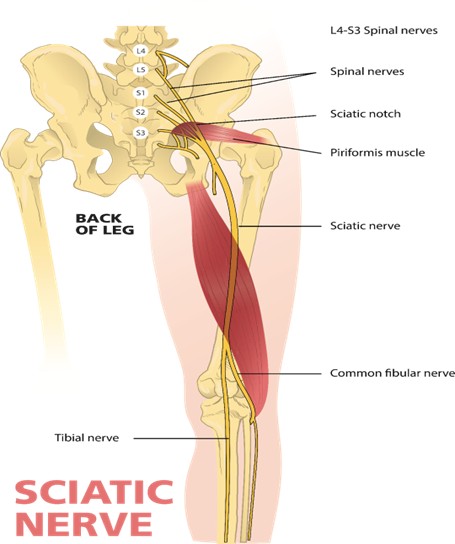

The central nerve that passes between the hamstring muscle group is the sciatic nerve. See the image below.

Whenever you bend or extend the hip or knee, this nerve needs to be able to slide and glide within its connective tissue sheath and the surrounding tissues. The body prioritises neural health over muscular function. When the nerve loses this sliding and gliding ability, protective muscular tension is the consequence.

To relieve this muscular tension, gentle manual neural manipulation of the sciatic nerve can have a profound and long-lasting effect.

Vascular Restriction:

Similar to the sciatic nerve, the femoral artery runs deep and central to the hamstrings, exiting between the distal heads. This artery is the main central artery of the leg. Just like a nerve, the femoral artery needs to be able to slide and glide within the surrounding tissues and possess good elastic properties to accommodate joint movement and the contraction of surrounding muscles. When this sliding, gliding, and elastic capability is compromised, hamstring tension

often results. When this occurs, vascular manipulation, rather than muscular massage or stretching, will achieve lasting relief.

Conclusion:

The causes of tight hamstrings are many and varied. As outlined above, the causes can be muscular, visceral, neural, vascular, strength, or movement-based. Rarely is there just one single cause. For lasting relief, it is essential that the correct causes are identified and the proper treatment approach implemented.